Iran's Last Monarch: Was The Shah Good For His Nation?

The reign of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, often simply referred to as "the Shah," remains one of the most contentious and debated periods in modern Iranian history. For decades, the question, "Was the Shah good for Iran?" has sparked passionate arguments, with proponents highlighting his ambitious modernization programs and opponents pointing to his authoritarian rule and the stark social inequalities that ultimately led to the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Understanding his complex legacy requires delving into the multifaceted impact of his policies on Iran's economy, society, and political landscape.

From his ascension to the throne in 1941 until his overthrow, the Shah steered Iran through a period of immense change, aiming to transform an ancient, traditional society into a modern, industrialized, and Western-aligned nation. His rule was characterized by significant economic growth, particularly fueled by oil revenues, and ambitious reforms. However, these advancements often came at the cost of political freedoms and widening social divides, laying the groundwork for the revolutionary fervor that would ultimately end his dynasty. This article explores the various facets of his rule to provide a balanced perspective on whether the Shah truly served the best interests of Iran and its people.

Table of Contents

- The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Westernization

- The Iron Fist: Repression and Political Control

- A Legacy Divided: Economic Disparities and Urbanization

- Foreign Policy and Geopolitical Role

- The Shah's Downfall: Seeds of Revolution

- Biography of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, The Last Shah of Iran

- Personal Data: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

- The Aftermath: Iran Without the Shah

The Shah's Vision: Modernization and Westernization

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi inherited a nation grappling with the aftermath of World War II and the lingering influence of foreign powers. His ambition was nothing short of transforming Iran into a regional powerhouse, a modern state capable of standing shoulder to shoulder with developed nations. His vision, often termed the "White Revolution" (Enghelāb-e Sepid), was a series of far-reaching reforms launched in 1963. These reforms aimed to address various socio-economic issues and accelerate Iran's development. The central question, "Was the Shah good for Iran" in terms of his modernization efforts, elicits mixed responses. On one hand, the country saw unprecedented development; on the other, the pace and nature of these changes created significant societal friction.

- Two Babies One Fox

- Truist One View Customer Service

- Discovering The Legacy Of Desi Arnaz Jr

- Alina Rose

- Samuel Joseph Mozes

The White Revolution encompassed land reform, nationalization of forests and pastures, sale of state-owned factories to finance land reform, profit-sharing for industrial workers, women's suffrage, and the creation of a literacy corps. These initiatives, while progressive on paper, often faced implementation challenges and generated discontent among various segments of the population. For instance, land reform, intended to empower peasants, often led to the creation of a new class of landless laborers who migrated to cities, swelling the ranks of the urban poor.

Economic Reforms and Oil Wealth

Under the Shah, Iran experienced a remarkable period of economic growth, primarily fueled by its vast oil reserves. The nationalization of the oil industry in 1951, though initially leading to a standoff with Britain, eventually gave Iran greater control over its most valuable resource. By the 1970s, as oil prices soared, Iran's GDP grew at an astonishing rate. The Shah invested heavily in infrastructure projects, including roads, railways, dams, and power plants. New factories were built, and industries like steel, petrochemicals, and automotive manufacturing began to emerge. Educational institutions, including universities and technical schools, expanded rapidly, aiming to produce the skilled workforce needed for a modern economy.

This economic boom led to a significant increase in the standard of living for many Iranians, particularly the burgeoning middle class. Access to modern amenities, consumer goods, and healthcare improved. Cities like Tehran underwent massive transformations, with new high-rises, highways, and a Westernized lifestyle becoming increasingly prevalent. The Shah's economic policies aimed to diversify the economy away from sole reliance on oil, though this goal remained largely unfulfilled by the time of his overthrow. The rapid influx of oil wealth also led to inflation and corruption, which disproportionately affected the poor and contributed to growing resentment.

- Antonetta Stevens

- Sophie Rain

- Ashley Loo Erome

- Exploring The Fascinating World Of Yololary Spiderman

- Breckie Hill Shower Video

Social Changes and Women's Rights

The Shah's reign brought about significant social changes, particularly concerning women's rights and education. Women gained the right to vote and hold public office in 1963, a landmark achievement in a traditionally conservative society. The Family Protection Law of 1967 (and its amendment in 1975) introduced progressive reforms such as restricting polygamy, granting women greater rights in divorce and child custody, and raising the minimum age for marriage. These reforms were revolutionary for their time and place, challenging traditional norms and empowering women in unprecedented ways.

Education was another area of focus. The literacy rate improved significantly, and access to education, including higher education, expanded for both men and women. Western dress codes became common in urban areas, particularly among the educated elite, and traditional veiling (chador) was actively discouraged, and at times, even banned in public institutions. While these changes were welcomed by many, particularly the educated urban population, they alienated large segments of the traditional and religious society who viewed them as an assault on Iranian-Islamic values. This cultural clash would become a major factor in the growing opposition to the Shah.

The Iron Fist: Repression and Political Control

Despite the outward appearance of progress and modernization, the Shah's rule was increasingly authoritarian. He centralized power, suppressed political dissent, and maintained control through a pervasive security apparatus. This aspect of his rule is often cited by those who argue against the notion, "Was the Shah good for Iran?" His regime systematically dismantled democratic institutions and stifled any form of opposition, whether from secular nationalists, communists, or religious figures.

Political parties were largely ineffective or banned, and the parliament became a rubber stamp for the Shah's decrees. Elections were often rigged, and genuine political participation was severely limited. This lack of political freedom meant that grievances, even legitimate ones, had no legitimate outlet for expression, forcing dissent underground and making revolutionary change almost inevitable.

SAVAK and Human Rights Concerns

The most notorious instrument of the Shah's repression was SAVAK (Sāzemān-e Ettelā'āt va Amniyat-e Keshvar), the national intelligence and security organization. Established with the help of the CIA and Mossad, SAVAK became synonymous with arbitrary arrests, torture, and extrajudicial killings. Its reach extended into all aspects of Iranian life, creating an atmosphere of fear and suspicion. Dissidents, intellectuals, religious leaders, and political activists were routinely monitored, arrested, and imprisoned. Reports from international human rights organizations detailed widespread abuses, including the systematic torture of political prisoners.

The existence and actions of SAVAK severely undermined any claims of the Shah's benevolent rule. While the government argued that SAVAK was necessary to maintain stability and counter communist or extremist threats, its brutal methods alienated a broad spectrum of the population and fueled deep-seated resentment against the regime. The fear of SAVAK meant that even private criticism of the Shah was risky, leading to a profound sense of injustice and a yearning for fundamental freedoms.

Suppression of Dissent

The Shah's suppression of dissent was comprehensive. Universities, traditionally centers of political activism, were heavily policed, and student movements were ruthlessly crushed. Labor unions were controlled by the state, and independent worker organizations were not tolerated. Religious figures who criticized the regime, such as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, were exiled or imprisoned. Newspapers and media outlets were censored, and freedom of expression was severely curtailed.

This systematic suppression created a pressure cooker environment. While economic prosperity might have appeased some, the lack of political voice and the pervasive fear of the security forces alienated intellectuals, the clergy, students, and a growing number of ordinary citizens. The Shah's belief that his modernization programs would naturally lead to political stability proved to be a fatal miscalculation. The more he pushed for Westernization and economic growth, the more he relied on repression to silence those who felt left behind or whose values were being eroded. This growing chasm between the state and society ultimately defined whether the Shah was good for Iran in the eyes of its people.

A Legacy Divided: Economic Disparities and Urbanization

While the Shah's economic policies led to significant overall growth, the benefits were not evenly distributed. The rapid urbanization, fueled by the migration of rural populations seeking opportunities in the cities, led to the growth of vast shantytowns around major metropolitan areas. These new urban dwellers, often lacking skills for the modern economy, faced poverty, unemployment, and inadequate housing. The stark contrast between the affluent, Westernized elite and the impoverished masses became increasingly visible and socially destabilizing.

The Shah's focus on large-scale industrial projects often neglected traditional agriculture, leading to food imports and a decline in rural livelihoods. Inflation, exacerbated by oil wealth, further eroded the purchasing power of ordinary citizens. This widening gap between the rich and the poor, coupled with a perception of corruption within the ruling elite, fueled popular discontent. Many felt that the immense oil wealth was not benefiting the majority of Iranians but was instead enriching a select few and funding the Shah's lavish lifestyle and military spending. This perception directly impacted the public's answer to "Was the Shah good for Iran?" as it highlighted the social cost of his modernization.

Foreign Policy and Geopolitical Role

The Shah pursued an assertive foreign policy, positioning Iran as a key ally of the United States in the Cold War and a regional power. Iran's military, heavily equipped with advanced American weaponry, became one of the strongest in the Middle East. The Shah saw Iran as the "policeman of the Persian Gulf," a bulwark against Soviet expansion and a guarantor of oil flow to the West. This alignment brought significant military and economic aid from the US, but it also tied Iran's fate closely to American interests, which many Iranians viewed as a continuation of foreign interference in their country's affairs.

His close ties with the West, particularly the United States, were a double-edged sword. While they provided security and facilitated modernization, they also alienated many Iranians who felt that the Shah was sacrificing national sovereignty for personal power and Western approval. The perception of the Shah as a puppet of the West, combined with his autocratic rule, contributed significantly to the anti-regime sentiment that culminated in the revolution. The question of "Was the Shah good for Iran" in terms of foreign policy often boils down to whether national security and development justified the perceived loss of independence and the suppression of domestic dissent.

The Shah's Downfall: Seeds of Revolution

The confluence of economic disparities, political repression, cultural alienation, and the Shah's perceived subservience to foreign powers created a fertile ground for revolution. By the late 1970s, a broad coalition of opposition forces, ranging from liberal intellectuals and secular nationalists to leftists and, most powerfully, the religious clergy, had coalesced against the regime. The charismatic leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, exiled but communicating with his followers through cassette tapes, provided a unifying ideological framework for the diverse opposition.

Mass protests, initially met with brutal force, escalated throughout 1978. The Shah, increasingly isolated and ill, failed to grasp the depth of popular discontent. His attempts at conciliation were too little, too late. The military, once his strongest pillar of support, began to fracture under the pressure of mass defections and public opposition. Ultimately, on January 16, 1979, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi left Iran, marking the end of the 2,500-year-old Persian monarchy and ushering in a new era for Iran. The answer to "Was the Shah good for Iran?" from the perspective of the revolutionaries was a resounding "no," leading to a complete overhaul of the nation's political and social structure.

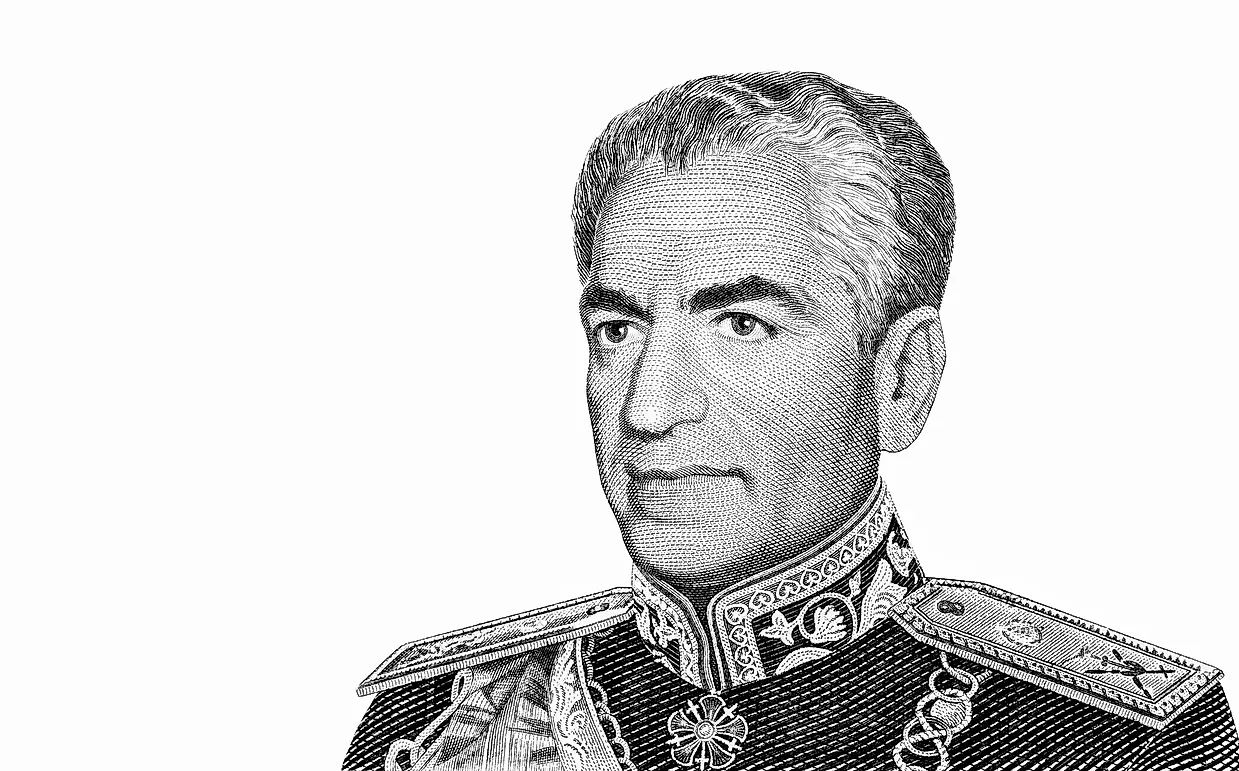

Biography of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, The Last Shah of Iran

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was born on October 26, 1919, in Tehran, Iran. He was the eldest son of Reza Shah Pahlavi, who founded the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925, transforming Iran from a Qajar-era kingdom into a modern, centralized state. From an early age, Mohammad Reza was groomed for leadership. He received his education in Switzerland, attending the Le Rosey boarding school, where he gained exposure to Western culture and ideas. This international upbringing profoundly influenced his later vision for Iran.

He returned to Iran in 1936 and enrolled in the Iranian Military Academy, graduating in 1938. His ascension to the throne in 1941 was precipitated by the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran during World War II, which forced his father, Reza Shah, to abdicate. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi thus became the Shah, a title (Shāh, title of the kings of Iran, or Persia) that had symbolized Iran's sovereignty and monarchical tradition for centuries. His early reign was marked by political instability and the struggle for control over Iran's vast oil resources, culminating in the 1953 coup d'état, which, with the backing of the US and UK, restored him to full power after a brief period of exile. From then on, he consolidated his authority, embarking on ambitious modernization programs but also increasingly relying on an authoritarian grip to maintain control, leading to the complex legacy that continues to be debated when asking, "Was the Shah good for Iran?"

Personal Data: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Mohammad Reza Pahlavi |

| Title | Shahanshah (King of Kings), Aryamehr (Light of the Aryans) |

| Reign | September 16, 1941 – February 11, 1979 |

| Born | October 26, 1919, Tehran, Iran |

| Died | July 27, 1980, Cairo, Egypt |

| Father | Reza Shah Pahlavi |

| Mother | Taj ol-Molouk |

| Spouses | Princess Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (m. 1939; div. 1948) Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary (m. 1951; div. 1958) Farah Diba (m. 1959) |

| Children | Princess Shahnaz Pahlavi Reza Pahlavi, Crown Prince of Iran Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi Prince Ali Reza Pahlavi Princess Leila Pahlavi |

| Education | Institut Le Rosey, Switzerland; Iranian Military Academy |

| Key Policies | White Revolution (Land Reform, Women's Suffrage, Literacy Corps), Industrialization, Military Modernization |

| Overthrown | 1979 Islamic Revolution |

The Aftermath: Iran Without the Shah

The departure of the Shah and the subsequent establishment of the Islamic Republic fundamentally altered Iran's trajectory. The revolution, while ending an autocratic monarchy, ushered in a new form of governance based on religious principles, leading to profound social, political, and economic changes that continue to shape Iran today. The question "Was the Shah good for Iran?" cannot be fully answered without considering the post-revolutionary era, which saw a shift from Western alignment to anti-Western sentiment, and from a secularizing state to a theocratic one.

The revolution was a complex phenomenon, driven by a multitude of factors, not just the Shah's perceived failures. However, his legacy remains central to understanding contemporary Iran. The rapid and often forced modernization, the suppression of political freedoms, and the widening economic disparities under his rule created a fertile ground for the revolutionary movement. While some look back at the Shah's era with nostalgia for its economic prosperity and perceived stability, others emphasize the human cost of his authoritarianism and the deep-seated grievances that eventually exploded into revolution. The ongoing debate about his rule underscores the profound and lasting impact he had on the nation.

Conclusion

The question, "Was the Shah good for Iran?" elicits a complex and nuanced answer, as his reign was a period of both remarkable progress and severe repression. On one hand, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi spearheaded ambitious modernization programs, leveraging Iran's vast oil wealth to build infrastructure, expand education, and advance women's rights. For many, particularly the urban middle class, his era represented a time of unprecedented economic growth and integration into the global economy, making life significantly better in many tangible ways.

However, these achievements were overshadowed by his increasingly autocratic rule, the pervasive fear instilled by SAVAK, and the growing social and economic inequalities. His relentless pursuit of Westernization alienated large segments of traditional society, while his suppression of political dissent left no legitimate outlet for opposition. Ultimately, the very policies intended to strengthen Iran created the conditions for a revolutionary upheaval that fundamentally reshaped the nation. His legacy remains deeply divisive, a testament to the profound and often contradictory forces that defined his rule and continue to influence Iran's path. We invite you to share your thoughts in the comments below: How do you view the Shah's impact on Iran? Or perhaps, explore other historical analyses on our site to broaden your understanding of pivotal moments in global history.

- Brandon Coleman Red Clay Strays

- Shawn Killinger Husband Joe Carretta

- Unraveling The Mystery What Happened To Dr David Jeremiah

- Exploring The World Of Roblox Condo Games A Thrilling Playground For Creativity

- Neil Patrick Harris Amy Winehouse Cake

U.S. Support for the Shah of Iran: Pros and Cons | Taken Hostage | PBS

Irfan Shah | ESPNcricinfo.com

Eight Facts About the Shah of Iran - WorldAtlas.com