Shah Of Iran: Good Or Bad? A Complex Legacy Unveiled

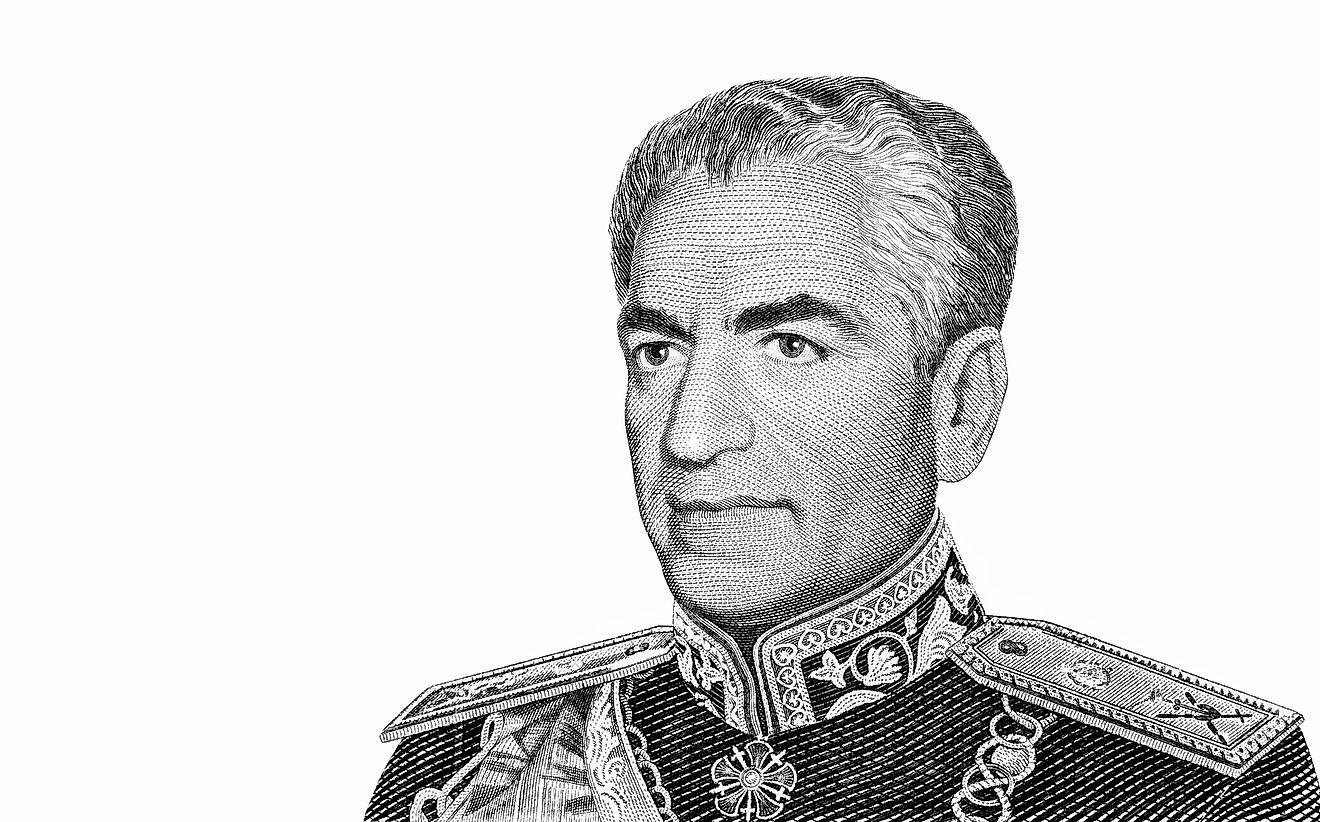

The question of whether the Shah of Iran was a force for good or ill is one that continues to spark fervent debate among historians, political analysts, and the Iranian diaspora. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, ruled for nearly four decades, overseeing a period of dramatic transformation, modernization, and, ultimately, revolution. His reign, marked by ambitious reforms and significant economic growth, was also characterized by authoritarianism, human rights abuses, and growing social unrest. Understanding his legacy requires a deep dive into the multifaceted aspects of his rule, examining both the progress he championed and the repression he oversaw.

To truly grasp the complexities of the Shah's era, one must look beyond simplistic labels of "good" or "bad." The title "Shāh," meaning "king," has been used by rulers of Iran, or Persia, for centuries, signifying a lineage of power and tradition. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi inherited this ancient mantle, but sought to modernize his nation, often clashing with traditional values and powerful religious institutions. This article aims to explore the pivotal moments, policies, and criticisms that shaped his controversial reign, offering a balanced perspective on a figure who remains central to Iran's modern history.

Table of Contents

- Mohammad Reza Pahlavi: A Biographical Sketch

- The Historical Backdrop: Iran Before and During the Shah of Iran's Reign

- The Case for "Good": Modernization and Progress Under the Shah

- The Case for "Bad": Authoritarianism and Human Rights Concerns

- The White Revolution: A Defining Policy

- The Fall of the Shah of Iran: A Revolution Unfolds

- The Shah of Iran's Legacy and Its Aftermath

- A Balanced Perspective: Weighing the Evidence

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi: A Biographical Sketch

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was born on October 26, 1919, in Tehran, Iran. He was the eldest son of Reza Shah Pahlavi, who founded the Pahlavi dynasty in 1925, effectively ending centuries of Qajar rule. From an early age, Mohammad Reza was groomed for leadership, receiving a modern education that included time in Switzerland at Le Rosey, a prestigious boarding school. This exposure to Western thought and culture would profoundly influence his later policies and vision for Iran.

- David Muir Wife

- Daisys Destruction An Indepth Look At The Controversial Case

- Ice Spice

- Low Income White Girl Eyes

- Exploring Kaitlan Collins Husbands Nationality A Comprehensive Insight

He ascended to the throne in 1941, during World War II, after the Allied forces, fearing his father's pro-Axis sympathies, forced Reza Shah to abdicate. His early years as Shah were marked by political instability and challenges to his authority, most notably from Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who nationalized the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. The Shah briefly fled the country in 1953 but was restored to power through a controversial coup d'état, widely believed to have been orchestrated by the British and American intelligence agencies (MI6 and CIA). This event cemented his reliance on Western support and deepened public resentment among certain segments of the population.

Throughout his reign, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi sought to transform Iran into a modern, industrialized nation, mirroring Western democracies in many aspects. He initiated ambitious development programs and fostered close ties with the United States. However, his autocratic style and suppression of dissent ultimately led to widespread discontent, culminating in the 1979 Iranian Revolution, which forced him into exile and brought an end to the Iranian monarchy.

Personal Data: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

| Attribute | Detail |

|---|---|

| Full Name | Mohammad Reza Pahlavi |

| Title | Shah of Iran (Shāhanshāh, "King of Kings") |

| Reign | September 16, 1941 – February 11, 1979 |

| Born | October 26, 1919, Tehran, Iran |

| Died | July 27, 1980, Cairo, Egypt |

| Predecessor | Reza Shah Pahlavi (Father) |

| Successor | Abolished Monarchy (Iranian Revolution) |

| Spouses | Fawzia Fuad of Egypt (m. 1939; div. 1948), Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary (m. 1951; div. 1958), Farah Diba (m. 1959) |

| Children | Shahnaz Pahlavi, Reza Pahlavi, Farahnaz Pahlavi, Ali Reza Pahlavi, Leila Pahlavi |

| Religion | Shia Islam (Nominally) |

The Historical Backdrop: Iran Before and During the Shah of Iran's Reign

To understand the "good or bad" debate surrounding the Shah of Iran, it's crucial to contextualize his rule within Iran's broader historical trajectory. For centuries, Iran had been a nation grappling with foreign influence, internal divisions, and a struggle to modernize while preserving its unique cultural and religious identity. His father, Reza Shah, had initiated a top-down modernization program, establishing a centralized state, building infrastructure, and secularizing institutions, often through authoritarian means. This laid the groundwork for Mohammad Reza's own ambitions.

When Mohammad Reza Pahlavi came to power, Iran was still largely an agrarian society with significant illiteracy rates and limited industrialization. The nation's vast oil reserves, though a source of potential wealth, were largely controlled by foreign entities, leading to a sense of national humiliation and economic exploitation. The early years of his reign were marked by a delicate balancing act between internal political factions, including nationalist movements and religious conservatives, and external pressures from global powers, particularly the United States and Great Britain.

The 1953 coup, which restored the Shah to full power, marked a turning point. With consolidated authority and robust American backing, the Shah embarked on an accelerated program of modernization and development. Iran became a key strategic ally for the West during the Cold War, serving as a bulwark against Soviet influence in the region. This alliance brought significant military aid and technological transfers, fueling the Shah's vision of transforming Iran into a regional powerhouse. The economic boom, driven by rising oil revenues, provided the resources for ambitious projects, but also created new social and economic fissures that would ultimately contribute to his downfall. The question of whether the Shah of Iran's methods justified the outcomes remains central to his historical evaluation.

The Case for "Good": Modernization and Progress Under the Shah

Proponents of the Shah's legacy often point to the significant strides Iran made under his rule in terms of economic development, infrastructure, and social reforms. His vision was to transform Iran into a modern, secular, and prosperous nation, capable of standing shoulder-to-shoulder with developed countries. Many of his policies aimed to achieve this ambitious goal.

Economic Development and Infrastructure

Under the Shah of Iran, the country experienced an unprecedented period of economic growth, largely fueled by its vast oil reserves and increasing global oil prices. The Shah invested heavily in industrialization, building factories, power plants, and modern infrastructure. Major projects included the construction of new roads, railways, ports, and airports, significantly improving connectivity and trade within the country and with the outside world. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) saw substantial increases, and per capita income rose, leading to a visible improvement in living standards for many Iranians, particularly in urban centers.

The oil industry was expanded and modernized, and the Shah successfully negotiated for a greater share of oil revenues for Iran. This wealth was then channeled into various development programs, including education and healthcare. New universities and hospitals were built, and access to basic services expanded. The urban landscape of major cities like Tehran was transformed with modern buildings, wide boulevards, and a burgeoning consumer culture, creating an impression of rapid progress and prosperity.

Social Reforms and Women's Rights

Perhaps one of the most frequently cited positive aspects of the Shah's rule was his commitment to social reforms, particularly regarding women's rights and secularization. Inspired by his father's earlier reforms, the Shah pushed for a more liberal society, challenging traditional religious norms. Women gained the right to vote in 1963, a significant milestone for the region. They were also encouraged to pursue education and careers, entering professions previously dominated by men, such as law, medicine, and engineering. The Family Protection Law of 1967 (later amended in 1975) significantly improved women's legal standing in matters of marriage, divorce, and child custody, limiting polygamy and giving women greater rights.

Education was a high priority, with the establishment of numerous schools and universities across the country. Literacy rates, though still a challenge, saw considerable improvement, especially among younger generations. The Shah also promoted a more secular lifestyle, encouraging Western dress and cultural norms, and diminishing the influence of the clergy in public life. For many, these reforms represented a progressive leap forward, bringing Iran closer to the modern world and offering new opportunities that were previously unimaginable.

The Case for "Bad": Authoritarianism and Human Rights Concerns

Despite the economic and social advancements, the reign of the Shah of Iran was deeply flawed by its authoritarian nature, widespread human rights abuses, and a growing disconnect between the ruling elite and the general populace. Critics argue that the benefits of modernization came at an unacceptable cost to political freedoms and social justice.

Political Repression and SAVAK

The most significant criticism leveled against the Shah was his increasingly autocratic rule and the brutal suppression of political dissent. Following the 1953 coup, the Shah systematically dismantled democratic institutions and concentrated power in his own hands. Political parties were banned, elections became largely ceremonial, and freedom of speech and assembly were severely curtailed. The press was heavily censored, and any opposition was met with swift and harsh retaliation.

At the heart of this repressive apparatus was SAVAK, the Shah's secret police and intelligence agency. Established with the help of the CIA and Mossad, SAVAK became synonymous with fear and torture. Thousands of political prisoners, including students, intellectuals, religious leaders, and activists, were arrested, interrogated, and subjected to systematic torture. Extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances were common. The pervasive fear of SAVAK created an atmosphere where public criticism of the Shah was almost impossible, driving dissent underground and fueling deep-seated resentment among a broad spectrum of Iranian society.

Wealth Disparity and Westernization Backlash

While the Shah's economic policies led to overall growth, the benefits were not evenly distributed. A significant wealth gap emerged between the urban elite, who often benefited directly from government contracts and Western connections, and the rural poor and urban working class. Corruption within the royal family and government circles was rampant, further exacerbating feelings of injustice and inequality. The rapid influx of oil wealth led to inflation, making basic necessities unaffordable for many, particularly those without access to the new economic opportunities.

Furthermore, the Shah's aggressive push for Westernization alienated large segments of the population, especially traditionalists and religious conservatives. The perceived erosion of Iranian and Islamic values, coupled with the lavish lifestyle of the royal family and the elite, was seen as a betrayal of the nation's identity. The imposition of Western dress codes, secular education, and cultural norms clashed with deeply held religious beliefs and traditions. This cultural alienation, combined with political repression and economic disparities, provided fertile ground for the rise of a powerful religious opposition, led by figures like Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who capitalized on popular grievances against the Shah of Iran.

The White Revolution: A Defining Policy

In 1963, the Shah of Iran launched what he termed the "White Revolution," a series of far-reaching reforms designed to modernize Iran from the top down and prevent a "red" (communist) revolution from below. This program was a cornerstone of his domestic policy and aimed to address some of the underlying socio-economic issues, while also consolidating his power and diminishing the influence of traditional landowning elites and the clergy.

Key components of the White Revolution included:

- Land Reform: This was the most significant aspect, aiming to redistribute land from large landowners (including religious endowments) to landless peasants. While initially popular, its implementation was often flawed, leading to the creation of many small, uneconomical plots and a mass migration of dispossessed peasants to overcrowded cities.

- Nationalization of Forests and Pastures: All forests and pastures were declared state property, aiming for better management and conservation.

- Sale of State-Owned Factories to Finance Land Reform: Government-owned factories were privatized, with their proceeds intended to fund the land redistribution program.

- Profit-Sharing for Workers: Industrial workers were mandated to receive a share of their company's profits, intended to improve their living standards and productivity.

- Women's Suffrage: As mentioned, women were granted the right to vote and hold public office.

- Literacy Corps: Young men and women fulfilling their military service were sent to rural areas to teach literacy, aiming to combat illiteracy in remote villages.

- Health Corps: Similar to the literacy corps, this initiative sent medical professionals to rural areas to provide healthcare services.

- Reconstruction and Development Corps: Focused on modernizing rural infrastructure and agriculture.

- Judicial Reform: Aimed at modernizing the legal system.

While the White Revolution brought about some undeniable progress, particularly in literacy and women's rights, its implementation also generated significant unintended consequences. Land reform, for instance, alienated the powerful clergy, who were major landowners, and disrupted traditional rural economies. The rapid pace of change and the top-down, authoritarian manner in which these reforms were imposed further fueled discontent, particularly among those who felt their traditional way of life or economic security was threatened by the Shah of Iran's grand vision.

The Fall of the Shah of Iran: A Revolution Unfolds

Despite his efforts to modernize and consolidate power, the Shah of Iran's reign began to unravel in the late 1970s. A confluence of factors, including deep-seated discontent over political repression, economic inequality, cultural alienation, and the Shah's perceived subservience to the West, created a volatile atmosphere. The catalyst for the revolution was the rise of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a charismatic Shia cleric who had been exiled by the Shah in the 1960s for his outspoken criticism of the regime.

Khomeini's message, disseminated through cassette tapes and a network of mosques, resonated deeply with various segments of Iranian society: the religious conservatives who felt their values were under attack, the urban poor who struggled with inflation and lack of opportunity, the intellectuals who yearned for political freedom, and the bazaaris (traditional merchants) who were wary of Western economic influence. He skillfully articulated a vision of an Islamic government that would restore justice, independence, and spiritual purity to Iran.

The protests began modestly in 1977 but rapidly gained momentum in 1978, escalating into mass demonstrations, strikes, and violent clashes with security forces. The Shah's attempts to quell the unrest through a combination of concessions and brutal crackdowns proved ineffective. His military, though well-equipped, was ultimately unwilling to fire on its own people on a scale necessary to suppress the uprising. International support for the Shah also waned as the human rights situation deteriorated and the revolution's popular base became undeniable.

Facing overwhelming opposition and a collapsing state apparatus, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, left Iran on January 16, 1979, ostensibly for a "vacation." His departure marked the effective end of the Pahlavi dynasty and the beginning of a new chapter in Iranian history. Two weeks later, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran to a triumphant welcome, ushering in the Islamic Republic.

The Shah of Iran's Legacy and Its Aftermath

The legacy of the Shah of Iran is profoundly intertwined with the subsequent trajectory of Iran. His rule, while bringing about significant modernization and economic growth, ultimately failed to create a stable, legitimate political system that could withstand popular discontent. The revolution that overthrew him was not merely a change in leadership but a fundamental transformation of Iran's political, social, and cultural fabric.

In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, many of the Shah's reforms were reversed. Women's rights were curtailed, secular institutions were replaced by religious ones, and the economy underwent significant restructuring. The new Islamic Republic, while initially promising freedom and justice, soon established its own form of authoritarianism, leading to further political repression and a new set of challenges for the Iranian people.

Today, the Shah's era is viewed through different lenses. For some, particularly those in the Iranian diaspora who fled the revolution, his reign represents a golden age of prosperity, freedom (relative to the post-revolutionary era), and Western alignment. They remember the vibrant cultural scene, the opportunities for women, and the sense of national pride associated with Iran's growing international stature. For others, especially those who suffered under his authoritarian rule or whose families were marginalized by his policies, he remains a symbol of oppression, inequality, and foreign domination. The debate over whether the Shah of Iran was "good or bad" continues to shape political discourse and national identity within and outside Iran, reflecting the deep divisions that persist regarding the nation's past and future.

A Balanced Perspective: Weighing the Evidence

Assessing whether the Shah of Iran was "good or bad" is an exercise in historical nuance, not a simple binary judgment. On one hand, he was a modernizer who dragged a largely agrarian society into the 20th century. He built infrastructure, expanded education, and championed women's rights to an extent unprecedented in the region. His vision for a powerful, prosperous Iran was ambitious, and he achieved significant economic growth, particularly through the leveraging of oil revenues. For many, especially the educated middle class and those who embraced a more secular lifestyle, his era represented progress and opportunity.

However, these achievements were overshadowed by his autocratic rule. The suppression of dissent through SAVAK, the lack of political freedoms, and the growing wealth disparity fueled a deep-seated resentment. His close ties with the United States were perceived by many as a form of neo-colonialism, undermining Iran's sovereignty. The cultural alienation caused by rapid Westernization further exacerbated tensions, leading to a profound cultural and religious backlash. The Shah of Iran, in his relentless pursuit of modernization, failed to cultivate a broad base of popular support or establish legitimate political channels for dissent, ultimately leading to his downfall.

Ultimately, the Shah's legacy is a complex tapestry of progress and repression. He was a ruler who genuinely sought to modernize his country but did so at the expense of political freedom and social justice. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of top-down modernization without popular participation and the inherent instability of regimes that prioritize economic growth over human rights and democratic principles. The "good or bad" debate will likely continue for generations, as each side grapples with the profound impact of his reign on the lives of millions and the subsequent trajectory of Iran.

What are your thoughts on the Shah's legacy? Do you believe his contributions to modernization outweigh the criticisms of his authoritarian rule? Share your perspective in the comments below, or consider exploring other articles on our site that delve deeper into the history of modern Iran.

U.S. Support for the Shah of Iran: Pros and Cons | Taken Hostage | PBS

Irfan Shah | ESPNcricinfo.com

Eight Facts About the Shah of Iran - WorldAtlas